By Christine Brennan, Ph.D. CCC-SLP, University of Colorado Boulder

Background

Telepractice in speech-language pathology has been around for at least 15 years [1], but due to school and clinic closures during the Covid-19 pandemic more therapy is now being provided via telepractice. Due to possible deficits in voice, speech, language, social communication, and cognitive development [2,3], many children and adults with Smith-Magenis Syndrome (SMS) receive and benefit from speech-language intervention. This study aimed to determine if parents/caregivers of children or adults with SMS believed that speech-language therapy provided via telepractice was more or less effective than in-person therapy.

Is Telepractice Effective?

Previous studies compared progress made by children (not diagnosed with SMS) given speech-language therapy in person versus via telepractice [4-8]. These studies collectively revealed similar progress made regardless of format and suggests that for many children, telepractice can be effective.

Methods and Results of the Online Survey Study

Information about speech-language therapy from parents and caregivers of children and adults with SMS was gathered from an online survey. Note that for the rest of this article, the terms “child” or “children” is used, even though some of the respondents provided information about their adult children with SMS.

To date, 20 parents/caregivers completed the survey. Parents/caregivers provided information for their children, ranging in age from 3-29 years (average age of 13 years).

The first three questions focused on routine, sleep, and behavior since the pandemic began.

- There were 19 responses about changes to the structure of their child’s daily routine: 74% (14/19) indicated it was now less structured, 21% (4/19) indicated it was about the same, and 5% (1/19) indicated the daily routine was more structured.

- There were 20 responses about changes to the amount of sleep their child gets: 55% (11/20) indicated there was no change, 20% (4/20) indicated less sleep, 11% (2/20) indicated more sleep, and 5% (1/20) was not sure.

- There were 20 responses about changes to their child’s behavior: 50% (10/20) indicated that behavior was worse, 30% (6/20) indicated that behavior was improved, and 20% (4/20) indicated that behavior had not changed.

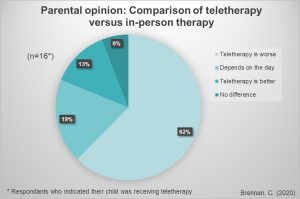

The next set of questions focused on speech-language therapy provided in person versus via telepractice. Sixteen of the respondents indicated their child had participated in teletherapy (telepractice) since the pandemic began.

- As a way to compare the effectiveness of therapy, the survey asked those parents/caregivers the following question: “Compared to previous in-person therapy sessions, how well do you think teletherapy is going?” Of the 16 respondents, 63% (10/16) indicated that teletherapy was worse, 19% (3/16) indicated teletherapy varied day to day, 12% (2/16) indicated that teletherapy was better, and 6% (1/16) indicated there was no difference.

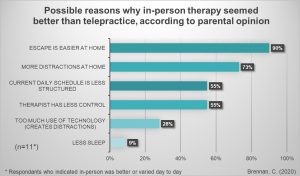

- Parents/caregivers who indicated that in-person therapy seemed better or varied day to day were asked to identify what they believed to be all of the contributing reasons (could pick more than one). Reasons included: easier means of escape (90%), distractions (73%), less structured daily routine (55%), therapist has less control (55%), technology use creates distractions (28%), and less sleep (9%).

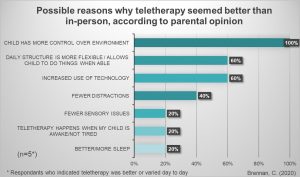

- Parents/caregivers who indicated that teletherapy seemed better or varied day to day were asked to identify what they believed to be all of the contributing reasons (could pick more than one). Reasons included: child has more control (100%), more flexible daily structure (60%), use of technology (60%), fewer distractions (40%), fewer sensory issues (20%), timing of session when child is well rested (20%), and more sleep (20%).

Compared to previous in-person therapy sessions, how well do you think teletherapy is going?

Parent/caregiver who indicated that in-person therapy seemed better or varied day to day were asked to identify what they believed to be all of the contributing reasons

Parent/caregiver who indicated that teletherapy seemed better or varied day to day were asked to identify what they believed to be all of the contributing reasons

Discussion

The preliminary results indicate that most of the individuals in this survey study did better with in-person therapy versus teletherapy. A small group of individuals with SMS reportedly did better with teletherapy. According to their parents/caregivers, teletherapy was better for some due to their children having more control over their environment, being engaged with the technology, having fewer distractions at home, and having a more flexible daily routine. In contrast, in-person therapy was reportedly better for others due to several consequences of teletherapy, including easier means of escape, more distractions at home, and the therapist having less control.

For individuals with SMS who do better with in-person therapy but are engaged in telepractice due to the pandemic, strategies that might improve these sessions include the following:

- Try to limit escape possibilities by changing the room or location, having another person present, if possible.

- Allow escape within a small space with the expectation that they child must “return” after the “break.” Try having the child stay in a room but he/she/they can ask for a short break and then move away from the computer or tablet for a couple of minutes. Use a timer to structure these breaks.

- Reduce the need for escape by slightly reducing task demands and by eliminating non-preferred tasks.

- Reduce distractions in the immediate environment (maybe have therapy in a different room or location).

- For individuals who need more structure, attempt to build more structure into the daily routine (use a schedule and rewards for following the schedule). Create a schedule of daily activities and allow the child with SMS to help make this schedule. Put preferred and necessary tasks into the schedule. Make sure that therapy is included into the schedule.

- If using a computer or tablet, reduce the apps or programs available to the individual with SMS.

- Use strategies to give the therapist more control without making the child feel like he/she/they are losing control. This can include home-based rewards for staying on task or “getting work done” during the session and by allowing the individual with SMS to choose the therapy activities from a selection given by the therapist (so the therapist has control but the child feels like he/she/they have control).

- Engage in therapy activities that the individual with SMS already finds enjoyable (preferred tasks).

- Try to schedule therapy sessions when the child with SMS will be best rested.

Conclusion

Although there is consensus that speech and language evaluations and services for individuals with SMS patients are necessary (Smith et al., 2001, 2012), there is no research regarding how this population responds to teletherapy in comparison to in-person therapy. The current study suggests that for some children with SMS teletherapy may be as effective as in-person therapy, however, research that directly tests therapy outcomes given teletherapy is still needed. Parents and providers should consider the role of individual factors and environment when planning the use teletherapy.

Final Note

Parents and caregivers should be aware that the survey is still posted and we are interested in having more people complete the survey. As more information is gathered, new reports will be shared on the PRISMS website.

Link to survey: https://forms.gle/DVoc6Rj11BSmmHBC9

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2005). Speech-language pathologists providing clinical services via telepractice: Position statement.

- Madduri, N., Peters, S. U., Voigt, R. G., Llorente, A. M., Lupski, J. R., & Potocki, L. (2006). Cognitive and adaptive behavior profiles in Smith-Magenis syndrome. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 27(3), 188-192.

- Smith, A. C., Dykens, E., & Greenberg, F. (1998). Behavioral phenotype of Smith‐Magenis syndrome (del 17p11. 2). American journal of medical genetics, 81(2), 179-185.

- Coufal, K., Parham, D., Jakubowitz, M., Howell, C., & Reyes, J. (2018). Comparing traditional service delivery and telepractice for speech sound production using a functional outcome measure. American journal of speech-language pathology, 27(1), 82-90.

- Boisvert, M., Hall, N., Andrianopoulos, M., & Chaclas, J. (2012). The multi-faceted implementation of telepractice to service individuals with autism. International Journal of Telerehabilitation, 4(2), 11.

- Grogan-Johnson, S., Alvares, R., Rowan, L., & Creaghead, N. (2010). A pilot study comparing the effectiveness of speech language therapy provided by telemedicine with conventional on-site therapy. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 16(3), 134-139.

- Grogan-Johnson, S., Gabel, R. M., Taylor, J., Rowan, L. E., Alvares, R., & Schenker, J. (2011). A pilot exploration of speech sound disorder intervention delivered by telehealth to school–age children. International Journal of Telerehabilitation, 3(1), 31.

- Grogan-Johnson, S., Schmidt, A. M., Schenker, J., Alvares, R., Rowan, L. E., & Taylor, J. (2013). A comparison of speech sound intervention delivered by telepractice and side-by-side service delivery models. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 34(4), 210-220.